Improving Emergency Department Opioid Treatment for People of Color

Medication for Opioid Use Disorder Addresses Racial Disparities in Michigan’s Hospitals

With more than 400,000 lives—and growing—claimed by opioid-related deaths, opioid use disorder is an ongoing public health crisis. Yet, attention to the opioid epidemic and its subsequent deaths have focused primarily on White suburban and rural communities even though people of color are bearing the brunt of its consequences.

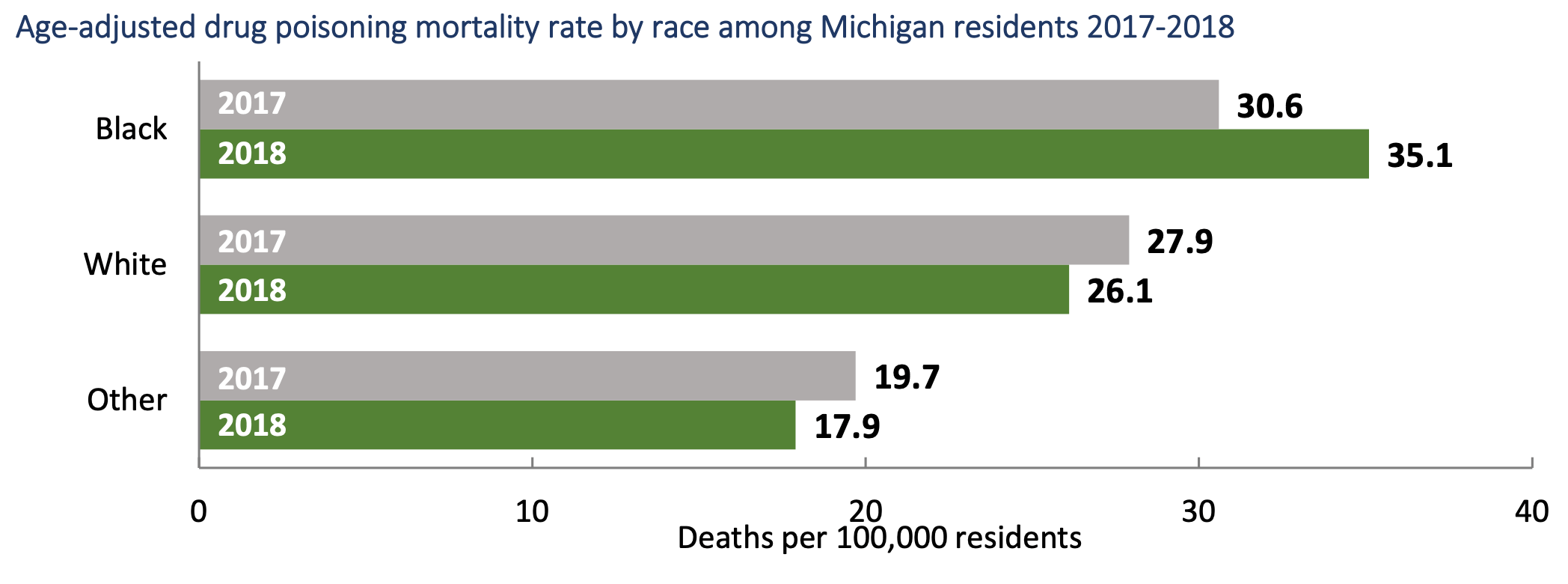

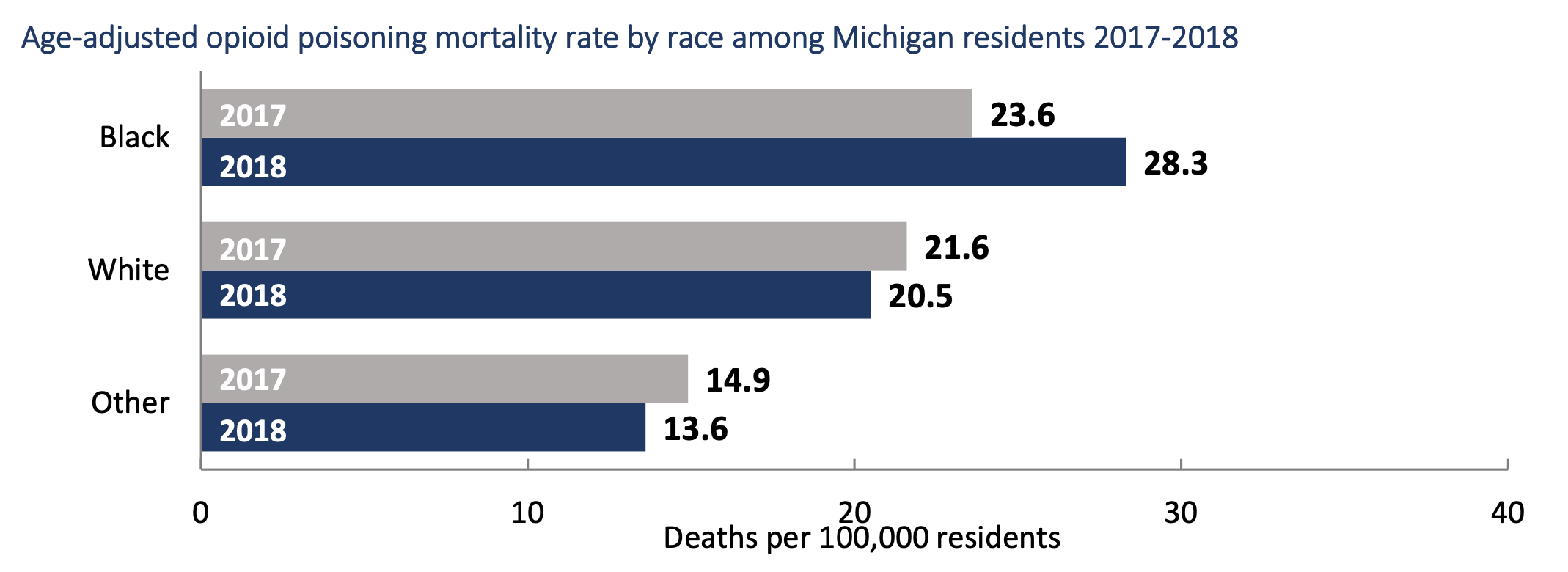

This is particularly true for members of the Black population. At 12.9 percent, they had the third highest opioid-related overdose death rate compared to other races/ethnicities in the country in 2017, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services reports that between 2017 and 2018, opioid mortality rates among Black residents increased by 19.9 percent while White residents saw a 5.1 percent decrease.

A provisional study released by the CDC confirms conditions for residents continued to worsen throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, with a 13.9 percent increase in overdose deaths among Blacks from 2019 to 2020.

Data Resources: Michigan Department of Health and Human Services

Increasing access through partnership

Leveraging the priorities of the Michigan Opioid Partnership, Vital Strategies collaborated with the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan to strengthen the capacity of hospitals and emergency departments, particularly in Wayne and Genesee counties, where overdose rates are among the highest in the state and where data shows the greatest racial disparities. Vital Strategies, a global public health organization, provided the foundation with the seed funds to work with emergency physicians in both counties to help them recognize their implicit bias and begin to address systemic racism in treating opioid use disorder (OUD).

Another impetus for the effort was the fact that even though medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) combined with behavioral therapy is an evidence-based treatment yielding impressive outcomes for people with OUD, it is not provided equitably to people of color. A Journal of American Medical Association Psychiatry letter written by researchers at the University of Michigan and the VA (Veterans Affairs) Ann Arbor Healthcare System published in 2019 found that Black patients are 77 percent less likely to receive buprenorphine—one of the more effective medications for the disease—than Whites in an outpatient setting. Further, when the medication is administered, Blacks are more likely to receive inadequate doses, diminishing the drug’s life changing results. According to Julie Rwan, Senior Technical Advisor at Vital Strategies, “The Black community in Wayne and Genesee counties is disproportionately impacted by overdoses. Our work is to assist practitioners in emergency departments with identifying people who could benefit from medication for opioid use disorder.”

Given the limited access to MOUD and the impact addiction is having on Black people, Amanda Reed, Analyst with the Health Initiative Team at the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, emphasizes the importance of “addressing the racial disparity issues that exist within our community.”

The foundation is working closely with New Detroit to design a training program for hospitals and emergency departments that will help health care providers engage more Black people in medication for opioid use disorder. New Detroit, a local racial justice organization, is a great partner for this work as they were already piloting a curriculum called Just Care, a general anti-bias training geared toward the health care sector.

New Detroit recognized that social determinants are not the only contributing factors to disproportionate health outcomes. Just Care specifically addresses racism, implicit biases, and stigma among health care practitioners as root causes of disparities related to treatment of people with OUD. Michael Rafferty, President and CEO of New Detroit, says the training program will result in emergency departments having more positive interactions and outcomes with Black patients seeking help with addiction. “How can we do everything that we can to make folks aware of their own bias? Everybody needs to participate in dismantling bias in health care.”

Treatment disparities anchored in history

Sara Lawson, Clinical Therapist

Overcoming health care provider bias is only one of the issues hindering access to quality care for OUD sufferers of color. Negative media portrayal of opioid use is another contributing factor. While the conversation about drug dependency is shifting from one of moral failure to chronic disease, coverage still often portrays White people with OUD as victims whose promise and potential have been co-opted by profit-driven drug companies. Conversely, Black people are depicted as remorseless criminals, lacking humanity.

Sara Lawson, a Black Family Development Clinical Therapist, who counsels emergency department patients seeking assistance with mental health and substance abuse treatment and advises on the Just Care curriculum, is often dismayed by the lack of sympathy and empathy health care providers show toward Black people.

“I often tell my coworkers they can’t judge a book by its cover,” Lawson says. “It’s not their place to criticize people who repeatedly come to the emergency room with the same problem. They don’t know how deep that person’s trauma is. Patients deserve respect.”

Punitive drug laws must also be curbed to close treatment gaps. According to Lawson, fear of incarceration is a primary reason why Black people do not seek treatment for addiction. She recalled a scenario involving a White woman under the influence of an opiate and caught by the police while driving with her children sitting on top of the car.

“She got probation,” Lawson exclaims. “Had that mother been Black, she likely would have gotten jail time and lost custody of her kids.”

Research seems to support Lawson’s prediction. According to The Changing Racial Dynamics of the War on Drugs, published by the Sentencing Project in 2009, two-thirds of people incarcerated for drug offenses were Black or Latinx despite representing less than one-third of the population and using drugs at a rate similar to Whites.

These practices and outcomes have been cultivated over the last 50 years through U.S. drug policy. While the federal government battled illicit drugs throughout the 20th century, modern attitudes regarding drug addiction have been shaped by The War on Drugs first declared by President Richard Nixon in 1971 and re-established by President Ronald Reagan in 1982. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, enacted during Reagan’s second term, resulted in mandatory and severe sentencing for low-level, nonviolent drug offenses, particularly related to cocaine, for a disproportionately high number of people of color. Federal laws held the same penalty for one gram of crack cocaine as 100 grams of the substance’s powder form. As crack was more common in Black communities, those caught using the drug received much harsher sentences than their White counterparts choosing cocaine.

The War on Drugs played to Americans’ worst fears about illegal drugs and was sold as a balm to what was ailing urban centers plagued by drug-related crime. It was later revealed that Nixon’s true motive for the initiative was to discredit both the Civil Rights and Anti-Vietnam movements of the late 1960s and early 1970s in an authoritarian attempt to quiet voices of dissent and distract the public from the issues these movements raised. The underlying racism became entrenched in the medical field with the crack epidemic of the 1980s, solidifying racist attitudes of hospital staff regarding who used drugs and where, permeating approaches to treatment in emergency departments across the country. Teaching health care providers about this episode in United States history is important, says Reed.

“A lot of the physicians in emergency departments are younger and may not understand the implications that these policies have had on people’s health outcomes and how they’ve shaped perceptions about Blacks,” she says.

Pathways to equity

The deleterious legacy of The War on Drugs must be dismantled to reverse the opioid epidemic’s trends. Fortunately, public health professionals at the community and institutional levels are beginning to work with health care providers on strategies that could enhance access to and engagement in MOUD among Black people.

Examine and deconstruct racial bias in emergency departments and hospitals.

Health care providers exhibit the same levels of implicit bias as the broader population. The primary difference, however, is that their negative evaluations of a person based on irrelevant characteristics like race can impact that individual’s health. Training them to recognize and confront the role identity, privilege, and perception play in how they treat people of color with OUD is a critical step toward equity and why programs like Just Care are so important.

Invest in a workforce that is qualified to respond to the clinical aspects of MOUD and the cultural needs of diverse populations.

Mounting evidence supports one of the best ways to address health care disparities is to develop a workforce that represents the client population. This is considered one of the main practices of cultural competency and enables institutions to function effectively with diverse communities. Compatibility between cultural backgrounds of staff and clients is thought to improve retention in treatment programs, helping OUD sufferers achieve full recovery.

Foster partnerships with grassroots organizations working close to the impacted population.

To improve the quality of care Black people with OUD receive, it is essential that stakeholders understand their needs. Before this can happen, health care professionals have to breakthrough long-held feelings of fear and mistrust, resulting from decades of discrimination and abuse. Community-based leaders can help overcome these issues and work to engage a broad cross-section of individuals, including policy makers, health care providers and administrators, patients, and advocates who are committed to making systemic change.

Implement a multi-layered approach to address opioid use disorder in traumatized communities.

Poverty, oppression, and violence have plagued Black people for centuries. Drugs became a way to escape the sense of hopelessness many of them faced. Employing a holistic methodology to address OUD that includes wrap-around services to meet patients’ most primal needs like food, housing, education, and employment is essential to resolving the crisis.

Improving access to culturally responsive and evidence-based treatments like MOUD is the only way to reduce the opioid epidemic’s impact on Black people. That requires collaboration and a commitment to equitable policies and services that cater to their needs.

“Racial equity work can’t be done in a silo. It is broad and requires intersectionality,” says New Detroit’s Rafferty. “Industry, philanthropy, and community all have to work together to create a vision of what racial justice in health care looks like and understand the biases that prevent us from achieving that vision.”

Learn more about the MOUD and the Michigan Opioid Partnership